A. Situation Report in Lesvos, as of 15/1/2020

- Total population of registered asylum seekers and refugees on Lesvos: 21,268

- Registered Population of Moria Camp & Olive Grove: 19,184

- Registered unaccompanied minors: 1,049

- Total Detained: 88

- Total Arrivals in Lesvos from Turkey in 2020: 1,015

Over 19,000 people are now living in Moria Camp – the main refugee camp on the island – yet the Camp lacks any official infrastructure, such as housing, security, electricity, sewage, schools, health care, etc. While technically, most individuals are allowed to leave this camp, it has become an open-air prison, as they must spend most of their day in hours long lines for food, toilets, doctors, and the asylum office. Sexual and physical violence is common – and three people have died as a result of violence and desperation in as many weeks. The Greek government has also implemented a new asylum law 1 January 2020 with draconian measures that restrict the rights of migrants. This new law expands grounds to detain asylum seekers, increases bureaucratic hurdles to make appeals, and removes previous protections for vulnerable individuals who arrive to the Greek islands. Specifically, all individuals that arrive from Turkey are now prohibited from leaving the islands until their applications are processed, unless geographic restrictions are lifted at the discretion of the authorities. These changes ultimately will lead to an increased population of asylum seekers trapped in Lesvos, and an increasing number of people trapped here who have had their asylum claims rejected and face deportation to Turkey. We will not detail here the current catastrophic conditions on the island for migrants, as they have already been detailed by others.

B. Legal Updates

Since the implementation of the new asylum law in Greece in January 2020, 4636/2019, it remains to be seen to what extent the Greek state will have the capacity to implement the various draconian provisions enacted into law. Below we have documented the following violations in the first few weeks of 2020, and procedural and practical complications in the implementation of the new law.

1. Right to Work Denied: According to article 53 of the Law 4636/2019, asylum seekers have the right to work six (6) months after they have submitted their asylum application, if they have not yet received a negative first instance decision. Under the previously enforced asylum law, 4375/2016, asylum seekers had the right to work with no limitations. However, as one of its first acts after the New Democracy party came into power in Greece, on the 11 July 2019 the Minister of Employment & Social Affairs, Mr Vroutsis, issued a decision stopping the issuance of social security numbers (AMKA) to asylum seekers (Protocol number: Φ.80320/οικ.31355 /Δ18.2084). Although the newly enacted law allows for the issuance of a “temporary insurance number and healthcare of foreigners” (Π.Α.Α.Υ.Π.Α.) to asylum seekers, under Article 55 para. 2, the joint ministerial decision regulating this has not been issued, and it has yet to be set in force. The possession of a Π.Α.Α.Υ.Π.Α. or AMKA is a prerequisite to be hired in Greece, therefore, it is practically impossible for asylum seekers who have not already obtained an AMKA to work and have access to healthcare, despite having the right to do so.

2. Access to Asylum Procedure Effectively Denied: According to article 65 para. 7 of the Law 4636/2019, there is a deadline of seven (7) days between the simple and full registration of an applicant’s asylum application. If the applicant does not present themselves before the competent authorities within 7 days, the case is archived with a decision of the head of the competent asylum office (article 65 para. 7 and 5). However, because of the number of asylum seekers currently living in Lesvos, many cannot access the asylum office on the day they are scheduled to register, as there are always hundreds of people waiting outside – and the asylum office is heavily guarded by the private security company G4S. This could lead to many people missing the deadline and being denied the right to apply for asylum. As a result their asylum cases could be closed, and they could face detention and deportation.

3. Risk of Rejection of Asylum Claims Due to Inability to Renew Asylum Seeker ID Card: For asylum applications being examined under the border procedure (the procedure implemented for all those who arrive to the Greek islands from Turkey), the renewal of the asylum seeker’s card must take place every 15 days, under article 70 para. 4(c) of law 4636/2019. With over 20.000 asylum seekers currently in Lesvos, it is nearly impossible for them to access the office in order to renew an asylum seeker card that is expiring. Some have reported they have to pay (20 Euros) to other asylum seekers who are ‘controlling’ the line just to get a spot on line, where they must wait overnight in extreme weather conditions. After implementing the new law for the first few weeks of 2020 and requiring renewal of asylum seeker’s cards every 15 days, the Lesvos Regional Asylum Office (RAO) realized this is a practical impossibility and returned to the former system of renewing every 30 days, as announced to legal actors via UNHCR this week. Despite this, it still remains extremely difficult to access the asylum office, given the demand. Often the assistance of a lawyer is needed just to book an appointment or get in the door. The consequences of failing to renew an asylum seeker card under the new legislation are extremely harsh – asylum seekers must appear at the asylum office within one day of the expiration date, otherwise the asylum seeker’s card stops being valid ex officio, according to article 70 para. 6 of law 4636/2019. Their asylum claim will be implicitly withdrawn under article 81 para. 2 law 4636/2019, and this implicit withdrawal will be considered a final decision on the merits of their asylum claim, under article 81 para. 1 of law 4636/2019, despite never having had their asylum claim heard (if the implicit withdrawal is prior to their interview). While it may sound like a technical and insignificant difference, receiving a final decision on the merits means that they would need to appeal this denial to the Appeals Committee, rather than simply requesting the continuation of their case – which as described below involves additional obstacles that are likely to be impossible to overcome for many asylum seekers.

4. Prioritization of Claims Filed in 2020: The new asylum law allows for the accelerated processing of asylum application under the border procedures – i.e. for all those who arrive to Lesvos from Turkey. As RAO and EASO transition to the new law, they have prioritized the processing of the asylum claims of new arrivals, at the expense of the thousands of asylum seekers who arrived and applied for asylum in Lesvos in 2018/2019. Those that have arrived in 2020 are registered and scheduled for interviews with the EASO within a few days of arrival. This means that it is extremely difficult for these individuals to access legal information or legal aid prior to their asylum interviews. Individuals who arrived last year, however, and are waiting months to be heard, are having their interviews postponed in order to accommodate the scheduling of interviews for new arrivals. We have also received information that EASO has not only prioritized new arrivals for interviews, but also prioritized the issuance of opinions for the cases of new arrivals, meaning that decisions for those who were interviewed in 2019 will also be delayed.

5. Delay in Designation of Vulnerabilities Results in Continued Imposition of Geographic Restrictions for pre-2020 Arrivals: The designation of vulnerability under the previous asylum law led to the lifting of geographic restrictions to Lesvos, as ‘vulnerable’ individuals were referred form the border procedure to the regular asylum procedure. Vulnerable groups, as defined by pre 2020 law included: unaccompanied minors; persons who have a disability or suffering from an incurable or serious illness; the elderly; women in pregnancy or having recently given birth; single parents with minor children; victims of torture, rape or other serious forms of psychological, physical or sexual violence or exploitation; persons with a post-traumatic disorder, in particularly survivors and relatives of victims of ship-wrecks; victims of human trafficking. In 2018, 80% of asylum seekers in Lesvos were designated vulnerable (or approved for transfer to another European State under the Dublin III Regulation), and therefore able to leave Lesvos prior to the final processing of their asylum claims. Under the new legislation, however, vulnerable individuals continue to have their asylum claims processed under the border procedures, as specified in article 39 para. 6 of law 4636/2019. Many individuals who arrived in 2019 and should have been designated vulnerable through the Reception and Identification Procedures’ mandatory medical screening, provided by Article 9 para. 1c of the law 4375/2016, were not designated as such in 2019 due to delays and failure to have a thorough medical screening. For example, just in the past two weeks we have met with survivors of torture, sexual assault and people suffering from serious illnesses who arrived to Lesvos months ago, but have not been designated vulnerable due to a lack of a thorough medical assessment. If designated vulnerable in 2020, the State is currently applying the new law to these individuals, and continues to process their claims under the border procedures, rather than lifting geographic restrictions and referring to the regular asylum procedure. They have now missed the opportunity to have geographic restrictions lifted while they await their interviews, through fault of the Greek state. We should also note that the new legislation also requires a medical screening under Article 39, para. 5 4636/2019, however, this does not carry the same legal consequences, as those found vulnerable under the new legislation are not referred from the border to regular procedure.

This week the Legal Centre Lesvos represented one couple from Afghanistan, in which the wife is pregnant (a category of vulnerability). In late 2019, they had been designated vulnerable and referred to the regular procedure, however, when in 2020 they were issued their asylum seeker card, it was with geographic restrictions. Only after the intervention of the Legal Centre Lesvos, were they advised that this was merely a ‘mistake’ and they would be referred back to the regular procedure and geographic restrictions would be lifted when they next renewed their asylum seeker card. Meanwhile, for the next two weeks they are unlawfully restricted to Lesvos.

6. Insurmountable Hurdles to Appeal Negative Decisions: Under the new legislation, asylum applicants who receive a negative decision must describe specifically the grounds in which they are making an appeal in order for their appeal to be admissible by the Appeals Committees, according to articles 92 and 93 of 4636/2019. This is practically impossible without a lawyer to assess the decision and determine the grounds of appeal. Although the state is obligated to provide a lawyer on appeal (article 71 para. 3), this right has been denied for over two years in Lesvos. Nevertheless, the Lesvos RAO appears to be enforcing the new provision of the law requiring individuals to provide the grounds for appeal in order to lodge an appeal, but continues to deny applicants lawyers on appeal in order to determine these grounds – meaning that many are practically unable to lodge an appeal. Others are physically blocked from even accessing the asylum office in order to lodge the appeal due to the hundreds of people attempting to access the asylum office at any given time. We have documented at least one case of a family with two small children, that were arbitrarily given a five day deadline to lodge their appeal and moreover they were unable to enter the asylum office despite trying every day. Only through the intervention of a Legal Centre Lesvos attorney – accompanying the family on multiple days – the family was able to access the asylum office in order to lodge their appeal in due time. Furthermore, it will be a practical impossibility to accompany every asylum seeker whose case is rejected, and many are or will likely miss the deadline to lodge their appeal, if practices are not immediately changed.

7. Denial of Interpreter for Detained Asylum Seekers Speaking Rare Languages at Every Stage of the Procedure: In November 2019, 28 asylum seekers’ claims were rejected with no interview having taken place, on the basis that no interpreter could be found to translate for them in their languages. The Legal Centre Lesvos and other legal actors represented these individuals on appeal, and denounced this illegal practice. Now, it appears the Lesvos RAO is attempting a new practice to reject the asylum claims of detained asylum seekers. Last week several men from sub-Saharan African countries who were detained upon arrival (based on the practice of arbitrarily detaining ‘low profile refugees’ based on nationality) were scheduled for interviews this week in either French or English, depending on whether they came from an area of the African continent that had previously been colonized by France or by Great Britain. This is despite the fact that they requested an interview in their native language, as is their right, under article 77 para. 12 of 4636/2019. The lasting effects of colonization – also a driving factor in continued migration from Africa to Europe – has continued to haunt these individuals, as even after they have managed to make it into Europe, they are now expected to explain their eligibility for asylum in their former colonizer’s language. The clear attempt to reject detained asylum seekers’ claims without regard to the law is a worrying trend, combined with the provisions of the new legislation which allow for expanded grounds for detention and expanded length of detention of asylum seekers. The Legal Centre has taken on representation of one of these individuals in order to advocate for the right of asylum seekers to be interviewed in a language they can communicate comfortably and fluently in.

8. Apparent Suicide in Moria Detention Centre Followed Failure by Greek State to Provide Obligated Care. On 6 January a 31-year-old Iranian man was found dead, hung in a cell inside the PRO.KE.K.A. (Pre-Removal Detention Centre) According to other people detained with him, he spent just a short time with other people, before being moved to isolation for approximately two weeks. While in solitary confinement, even for the hours he was taken outside, he was alone, as it was at a different time than other people. For multiple days he was locked in his cell without being allowed to leave at all, as far as others detained saw. His food was served to him through the window in his cell during these days. His distressed mental state was obvious to all the others detained with him and to the police. He cried during the nights and banged on his door. He had also previously threatened to harm himself. Others detained with him never saw anyone visit him, or saw him taken out of his cell for psychological support or psychiatric evaluation. Healthcare in the PRO.KE.K.A is run by AEMY (a healthcare utility supervised by the Greek state). Its medical team supposedly consists of one social worker and one psychologist. However, the social worker quit in April 2019 and was never replaced. The psychologist was on leave between 19 December and 3 January. The man was found dead on 6 January meaning that there were only two working days in which AEMY was staffed during the last three weeks of his life, when he could have received psychological support. This is dangerously inadequate in a prison currently holding approximately 100 people. EODY is the only other state institution able to make mental health assessments, yet it has publicly declared that it will not intervene in the absence of AEMY staff, not even in emergencies, and that in any case it will not reassess somebody’s mental health. For more details, see Legal Centre Lesvos publication, here. Of note is that there is no permanent interpretation service inside the detention centre.

C. Legal Centre Lesvos Updates

Despite the hostile political environment in Lesvos, a few significant successes confirm the importance of continued monitoring, litigation, and coordination with other actors in advocating for migrant rights in Lesvos.

- On 25th November 2019 we joined other legal actors on Lesvos in representing 28 men from African countries whose asylum claims were rejected before they had even had an interview on their claims. These individuals – through the long denounced ‘pilot’ project – were arbitrarily detained upon arrival to Lesvos from Turkey, based only on their nationality – as they are from countries with a ‘low refugee profile.’ The RAO further denied these individuals their rights in November 2019, when their asylum claims were rejected on the basis that there was a lack of interpreter to carry out the interviews. In the case of the Legal Centre Lesvos client, he was rejected because apparently a Portuguese interpreter could not be found! We collaborated with other legal actors on the island and UNHCR in representing these individuals on appeal, and engaging in joint advocacy to denounce this illegal practice. Following this joint advocacy initiative, the Lesvos RAO has continued the illegal practice of arbitrary detention based on nationality, and has attempted new tactics to accelerate the procedure, rejection, and ultimate deportation of these individuals (as described above), but there have been no reports of denial of asylum claims based on lack of interpretation since our joint advocacy in November 2019.

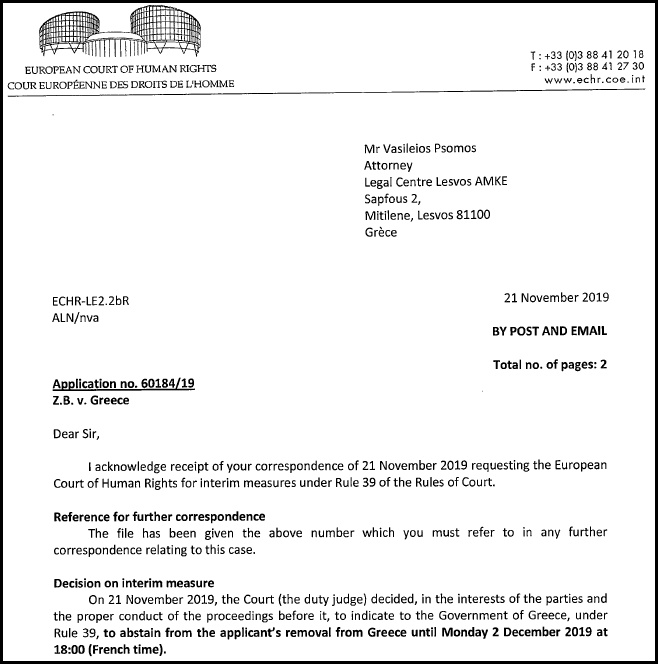

- Following our successful submission to the European Court of Human Rights in November 2019, which led to the last minute halting of a scheduled deportation, the police appeared to have changed their policies. In the month prior to our filing, at least six individuals were deported to Turkey, after having filing appeals in administrative court, and motions to suspend their deportation pending resolution of their appeals. Despite the fact that the administrative court had not yet ruled on the suspension motions, these individuals were forcibly deported to Turkey. Since our petition to the ECHR, in which we raised the lack of effective remedy in Greece, there have been no reported cases of deportation of individuals who have filed administrative appeals on their asylum claims. Our efforts in making this change were not alone, as advocacy from other legal actors and the Ombudsman’s Office against this practice likely contributed to the changed policy.

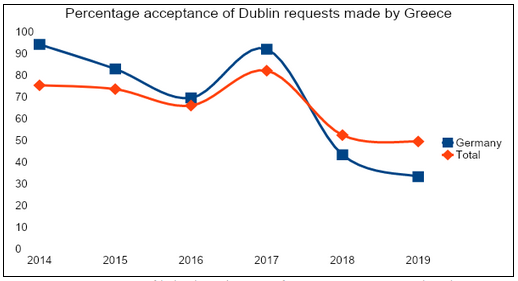

- Dublin Successes in Increasingly hostile climate: Since late 2017, there has been an increase in the number of refusals of ‘take charge’ requests for family reunification sent by the Greek Dublin Unit to Germany under the Dublin III regulations, with a variety of reasons used to deny the reunification of families who have often been separated by war and persecution. The family reunification procedure under the Dublin regulations is one of the rare legal routes protecting family unity and allowing for legal migration for asylum seekers out of Greece to other European states.

Source, Greek Asylum Service

In the period of October 2019 – December 2019 four families we represented had their applications for family reunification through Dublin III Regulations approved, enabling our clients to reunite with family members in France, Germany, and Sweden.

- Our most recent Dublin success involved the reunification of a family with two minor sons who are living in Germany. The two minor sons had left Afghanistan 5 years ago and had been separated from their family ever since. There is a trend from the German Dublin Unit to reject the cases in which families make the difficult decision to first send their minor children to safety when the entire family is not able to leave together. The German Dublin Unit has denied these cases on the basis that it is not in the best interest of the child to reunite minor children with parents who used smugglers to send their children to safety. We have consistently argued that when the children’s life is at risk, the parents should not be punished for using whatever means they can to find safety for their children, when legal and safe routes of migration are denied to them. The German Dublin Unit agreed in this case after advocacy from the Legal Centre Lesvos and the Greek Dublin Unit.